ILFORD XP2 Super in black and white chemistry Posted On 24th March 2018 To Magazine & Film specific

An experiment in chemical possibilities

When I took up a camera after a few years’ hiatus in 1990, I was surprised to discover that I could no longer get a black & white film developed through the nearest camera shop, never mind through the local pharmacy. If memory serves, I was told it would cost $40 for a single film. Naturally, I returned to processing my own film just I had done when I first took up a camera in the early 1970s. The world had moved on, and colour film was the default medium for the general population, even though it was more complex and more expensive; economies of scale had made the less popular B&W film become more expensive.

It was against that background that chromogenic B&W films were introduced by Kodak, ILFORD and Fuji (the Fuji version is almost certainly made by Ilford, and very likely the same emulsion). These provided the photographer a way of using a B&W film that could be developed at any minilab in the local camera shop, drugstore or supermarket. I don’t know, but I imagine they weren’t wildly popular as surely most people needing to record a scene with a photograph—I don’t say ‘photographers’—would certainly opt for colour at the same price. I have continued to develop my own films, whether B&W, colour negative or reversal. Having cut my photographic teeth in an era when film was the only option (OK, I could have used glass plates or tintypes!) I was used to the prevailing concept that grain was a nearly unavoidable evil, especially with faster films. Digital didn’t exist, and no one ‘added grain’ to mimic the look of film, nor did film users emphasize grain just to show that they were using film. You tried to minimize the grain because it got in the way of the image. That has stuck with me, and incredibly gritty images irritate rather than impress me. So that’s why I have explored the use of a chromogenic film where the image is formed mostly of dye clouds that appear in response to the exposure of the tiny amount of silver present – this offers very fine-grained negatives. But wait a minute, doesn’t that mean using the C-41 colour chemicals that are more expensive and a bit more demanding in temperature control? Well, no, it doesn’t mean that at all. It turns out that chromogenic films can be developed in B&W chemistry, and even better, they can be pushed and pulled just as traditional silver halide films can, all the while keeping their low grain qualities!

A lucky accident

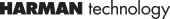

Like many discoveries, this one began with an accident. One day I had two films to develop, one B&W and one colour negative. I put them and two developing tanks into a changing bag and you can guess the rest. The colour negative film ended up being developed as if it were the B&W film. Other than being B&W, it ended up OK (All of the photo's below can be viewed full size on Flickr):

Kodak Ektar 100 developed in TMax developer

This got me thinking – low grain, but an expensive film to use just for conversion to B&W. I had read of people getting very nice results with XP2 Super (I’ll just call it XP2 in future to save time, but I do mean the current version of the film, not the original) with stand development using Rodinal 1+100, so I had to try it out. It turned out very nicely, especially if shot at EI 200, which gave a lot less grain that EI 400:

XP2 @EI 200, Rodinal 1+100 for one hour

This worked consistently, but spending an hour developing rather than a few minutes was a bit of a pain, so I tried some other developers. Next was Diafine, that jack of all trades that usually gives a speed boost and exacerbates grain as it does so. It worked at both EI 200 and EI 400, but neither had the fine grain I wanted:

XP2 @EI 200 in Diafine

XP2 @EI 400 in Diafine

I even ended up using some oddities, like the monobath invented by Donald Qualls, which was really gritty:

XP2 @EI400 in Qualls’ monobath

Eventually I tried Kodak HC-110, initially using Dilution E (1+47), but later swapping to 1+49 as it makes the mental arithmetic easier. This started to give me my best results yet. I started out at 8 minutes development:

XP2 @EI 400 in HC-110 1+49 for 8 minutes

Good, but the scans were a bit dark with a histogram crowded to the left, so I extended the development to ten minutes:

- XP2 @EI 400, in HC-110 1+49 for 10 minutes

- XP2 @ EI 400 in HC-110 1+49 for 8 minutes

It was at this stage I decided to see what might be done in terms of pulling and pushing. XP2 has quite some tolerance for over and under exposure and Ilford says it can be exposed at EI 50 – 800, and developed as usual in C-41 chemistry – obviously, the results will not be perfect but it might get you a photo that otherwise would have to be foregone. But if I’m using HC-110, why not try adjusting the development times just as you would for a silver halide film? I guessed some times using the rule of thumb that halving or doubling exposure time should result in a developing time that increases or decreases by one third, and have modified those a bit as I have gone along. The first experiment was to pull to EI 200, and I took an uninteresting photo to see if the method would decrease contrast so as to allow detail in a dimly lit room at the same time as some in the sunshine through a window:

XP2 @ EI 200 in HC-110 1+49 for 4 minutes

So off I went in the opposite direction to EI 800:

XP2 @ EI 800 in HC-110 1+49 for 13.5 minutes

The next experiment was EI 1600:

XP2 @ EI 1600 in HC-110 1+49 for 18 minutes

This surprised me, as it was still a very smooth picture and not overly contrasty. So I tried for 3200:

XP2 @ EI 3200 in HC-110 1+49 for 24 minutes

A ridiculously smooth-grained result for 3200! However, there was a problem, and that was that many frames of the film were simply black. I realized I was working right at the toe of the development curve, and any underexposure would fail to create an image at all. Consequently, I can’t really recommend using it at 3200, though I am going to do some more experiments. This example is on 120 film, and the one time so far that I have tried 35mm XP2 at 3200 I got pretty grainy results. Jobs still to do include another try of that with a camera with a more reliable meter than that in the Rolleiflex GX used above, and perhaps a try at a speed halfway between 1600 and 3200, say 2400 or 2500 depending on what my meter lets me use.

The final, and perhaps the most pleasing step was to pull the film to EI 100, resulting in some beautiful tones. This is in dull natural light:

XP2 @ EI 100 in HC-110 1+49 for 5 minutes

As is this:

XP2 @ EI 100 in HC-110 1+49 for 5 minutes

This one is taken with a bounced flash:

XP2 @ EI 100 in HC-110 1+49 for 4 minutes

My developing technique

All development was either in a standard Paterson or Nikor tank, at 20ºC, using six initial inversions and four more every minute thereafter. Lately, I have been using a motorized Rondinax tank, and the continuous agitation doesn’t seem to affect the times much at all.

My current thinking is this:

EI 25 3 minutes (not yet tested)

EI 50 4 minutes

EI 100 5 minutes

EI 200 6.5 minutes (could probably go to 7)

EI 400 10 minutes

EI 800 13.5 minutes

EI 1600 18 minutes

EI 3200 24 minutes (not reliable!)

One more curious point has turned up – someone else tried this out and got streaky negatives that were corrected by re-fixing. It might be that his fixer was exhausted, but I should note that I use ILFORD Rapid Fixer which comes in one liter bottles and is to be diluted 1+4. But, my Datatainer storage bottles are one US gallon in size, so my fixer ends up a bit stronger, about 1+3. It might be that I was lucky to avoid a problem just by that chance, and it might be that this regime requires a bit longer than five minutes of fixing if using fixer of normal strength.

I think it would be nice if Ilford would sanction this method of developing XP2 Super, as it would increase use of the film among home developers – and anything that sells film is good for all of us!

Technical notes

I have used a couple of techniques that might be non-standard to help me along the way. When assessing whether a development time is giving the right density in the negative I have not used a densitometer under an enlarger, I have scanned the negative with a Hasselblad X1 scanner and looked at the unmodified histogram. If, for example, the curve on the histogram is shifted to the left, the image will be dark, so the negative it came from will be too light, and could do with more development time to make more metallic silver thus darkening the negative and lightening the final image. I don't know if this is right, but I can't see why it would be wrong. Certainly, a negative that scans with the resultant histogram sitting nicely centered makes for a pleasing image.

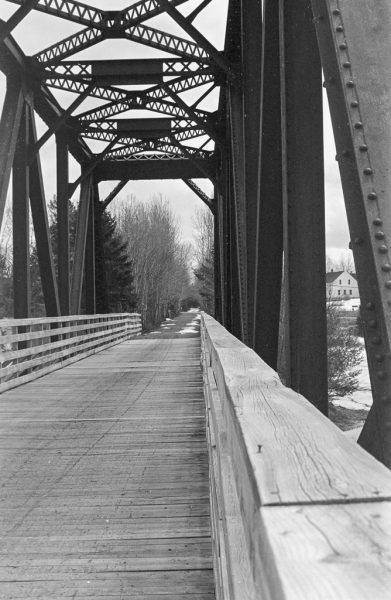

The second thing I have done is to assume, I hope correctly, that there will be some form of relationship between the exposure index used and the developing time required. I have mentioned the rule of thumb that doubling or halving exposure might reduce or increase development time by 33% respectively. Being a rule of thumb it provides a starting point. As I have gone along, I have made a graph of times that seem good for certain E.I.s, and roughly drawn in the curve by hand:

Pushing the boundaries

Today I am going to try a roll of XP2 at EI 2500 for the first time. If that graph means anything, it ought to require about 21.5 minutes in the developer. I will post results and see if that's roughly right.

Later: I'm not terribly pleased with XP2/35mm at 2500. Thin negatives and rather grainy. The whole film 'came out' with no blank/black frames, but they all look as if they need a lot longer in the developer. This is the best of them:

Seems I should accept that I can prove the worth of this film at 100 - 1600 so far. Time for me to pull it further and see if there any benefit in going down to ISO 50 or even ISO 25. ISO 100 is gorgeous, so maybe it won't be worthwhile, but someone's got to do it!

Back to ISO 100

I did another roll at ISO 100 - this film absolutely sings at this speed, with gorgeous rich tones:

Even slower

And now my first roll at ISO 50, developed for four minutes in 1+49 HC-110 in a motorised Rondinax. This looks nice too, but probably no better than ISO 100.

Shooting in snow

With snow down there's plenty of light, so I exposed another roll of XP2 at 100:

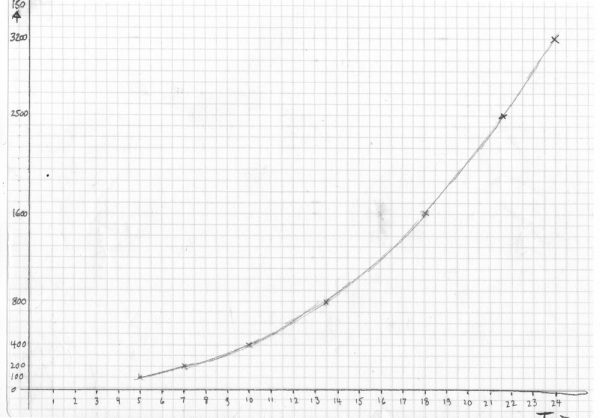

And then I finished off the roll with some indoor portraits using a strobe:

Beautiful tones and easy to scan. I now have a bottle of Ilfotec HC on the way and will repeat some of these speeds and development times with it to ensure that it works just as well as HC-110. That might earn Ilford's official approval!

ILFORD ILFOTEC HC

The bottle of Ilford Ilfotec HC has arrived, and the first roll of XP2 Super has gone through at EI 800:

Moving on from 800, this film was exposed at 1600 and developed in Ilfotec HC:

These next two images were at ISO 400 in Ilfotec HC for 10 minutes, using 120 XP2 Super in a Pentax 645n:

And these final two were 120 XP2 Super exposed at ISO 200 and developed in Ilfotec HC:

(That older iMac is how I keep backups of my photography. There are four 8TB disks in that drive, and they are set to automatically update one to another each day. On top of that drive is a dock for naked 3.5" disks, and I have about seven of them that I drop in and update weekly. A couple are kept elsewhere in case of fire. What you don't see is the Epson P600 printer on the floor under the Brother MFC and HP 7600. It's the best A4 and A3 printer I have ever had).

© Christopher Moss 2018

About The Author

Chris Moss

Chris Moss is a retired family physician in Nova Scotia who has been using film for nearly fifty years, in formats from half-frame all the way up to 10×8. He rather wishes Ilford would sell him XP2 Super in sheet formats!”