Penguins are black and white Posted On 15th August 2023 To Magazine & Stories

What it’s like to be a penguin

Possession Island is a rock in the Southern Indian ocean, about the size of the Scottish Isle of Rùm. It harbours a small French research station (a couple dozen people year round), and half a million seabirds. We have been monitoring King penguin populations there for the past decades: fascinating birds, King penguins. They may look clumsy on shore, but each of these little characters has been scouring through the wildest seas in the world, year in and year out, weathering colossal storms in search for silvery, juicy, shiny lantern fish.

And of course, as almost all wild animals or plants (all that hasn’t found a trick to cope with us), the seabirds of Possession Island are taking the hard blow from human presence on earth: ocean warming, shifting winds, chaotic ocean currents, accumulated contaminants, all that’s hiding under the surface of a seemingly pristine seabird haven. But that’s a story for another day. Today I had rather tell you what it’s like to be a penguin.

Newly formed King penguin couples. ILFORD Delta 400, Zeiss Jena Sonnar 180mm f/2.8 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter.

One in ten thousands

Faced with a penguin colony, you are first awed by the numbers - it may be like walking through Paris, Istanbul or Tokyo - people everywhere, faces without names, movement in every direction. After a while, you start to notice: tiny, tall, proud, tired. Passer by, busy heading somewhere, loiterer. Young or old, happy or sad. And you realise that little by little birds have become people, and each of them a single person in the crowd.

A breeding penguin heading out to sea after leaving the egg with its partner. ILFORD Delta 400, Zeiss Jena Flektogon 50mm f/4 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter.

ILFORD Delta 400, Canon EF 24-105 f/4 L IS USM II.

A different idea of focus

As a researcher, I use images all the time: aerial photos to count birds, time-lapse images to figure out their movement patterns, microscopy images for blood cell analysis, photo identification databases. I keep struggling for focus, sharpness and resolution - the aim is to cram as much fact as I possibly can into the camera sensor - but I end up with facts, not with sensations. What is it like to be a penguin walking through a metropolis, with blurry eyes that are razor-sharp under water, but misty on land? to stumble on half guided by sound, smells, and the sheer habits of the feet? What does it feel like to pick up the whistling of your baby calling out to you a hundred meters away, through a thousand other voices?

I often find that the narrow focus of a tilted or wide-open lens, and the wide, vibrating swathes of silver grain beyond focus give us a much more accurate idea of that feeling. There are things, many things going on, walking, moving, calling in every direction, and there in the middle there is that one point of focus that made one single penguin swim home: that one partner, that one egg, that whistling baby, that personal, untold life story.

ILFORD Delta 400, Zeiss Jena Sonnar 180mm f/2.8 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter, double exposure.

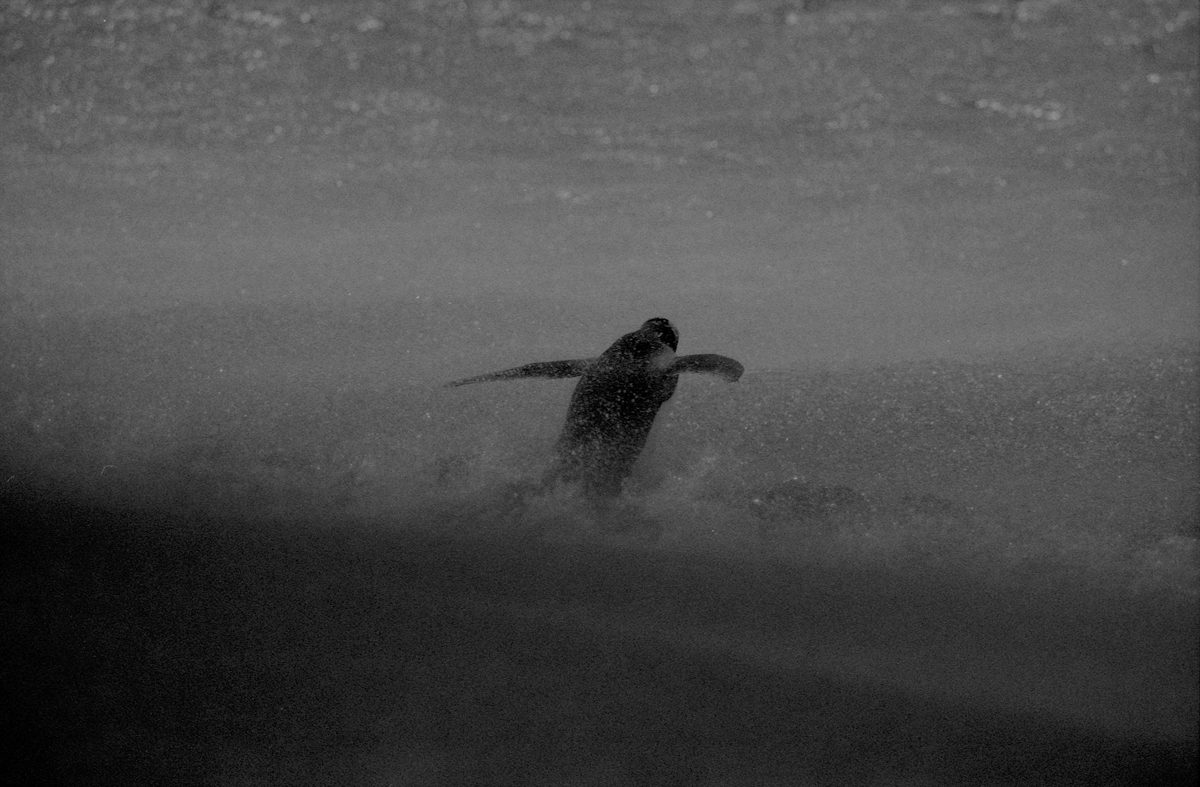

A penguin heading out to sea in a storm. ILFORD Delta 400, Canon EF 100-400 f/4.5-5.6 L IS II.

A young penguin begging for food from its parent. ILFORD Delta 400, Volna 3 80mm f/2.8 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter.

Evolution’s best graphic design

One other thing never stops fascinating me - the King penguin’s absurd graphical perfection. Past the flashing orange ear-patches and pink-purplish beak ornaments, penguins have invented the richest kaleidoscope of grays - softly melting tones structured by bold black streamlines, contrasting head patterns, pure white highlights… and of course, as you sit by the colony and let your eyes wander out of focus, you realise that these patterns make perfect sense: in a soft haze, gray tones and black lines take over our sense of dimensionality, each bird, each posture stands out, and a simple order shines through where attention to detail revealed only chaos.

A penguin sun-basking on the beach. ILFORD Delta 400, Canon EF 100-400 f/4.5-5.6 L IS II.

The whole Southern Ocean is black and white

I’ve always loved black and white film - but the Southern Ocean and Antarctica haven’t done much to prove me wrong, either. You know you sailed out of temperate waters the morning you walk out on decks and find the sea steel gray - both the blue and the white are gone, and even the sun is a light, matte gray on the back of the waves. From that day on, every albatross, every killer whale, every cloudy sky seems etched out of tarnished silver. I think this is how I came to love Delta - I often feel it’s the only film that pays its due tribute to the infinite variety of middle grays.

A sheathbill contemplating its own footsteps on the shore. ILFORD Delta 400, Zeiss Jena Sonnar 180mm f/2.8 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter.

A killer whale surveying the colony. ILFORD Delta 400, Canon EF 100-400 f/4.5-5.6 L IS II.

Stormy sunrise over the Île de l’Est. ILFORD Delta 400, Zeiss Jena Sonnar 180mm f/2.8 medium-format lens, mounted on the Ukrainian Arax tilt-shift adapter.

About The Author

Robin Cristofari

Robin Cristofari is a biologist at University of Turku, in Finland, and a part-time photographer alongside his field missions (here with the French Polar Institute). As a researcher, he is mostly exploring how climate and genome interact to determine the grim future of seabirds on this planet. As a photographer, he is perhaps mostly scared of the day there will not be any giant seabird metropolis to look at – and he does his best to document how it has been, to be there and watch them exist.