The Queering of Photography Posted On 27th June 2023 To Magazine & Stories

Queer Representation

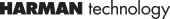

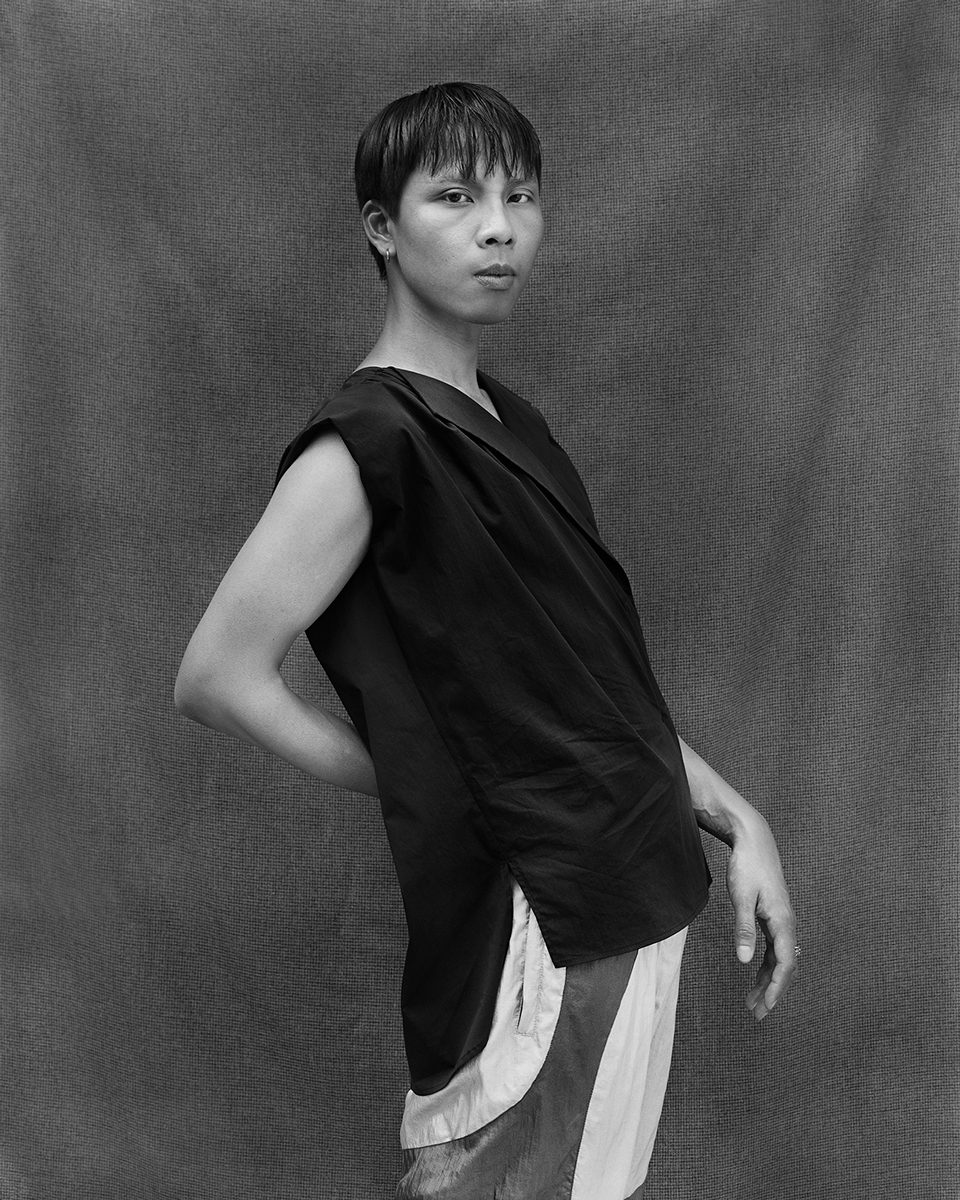

I made the first photograph for The Queering of Photography in 2015. I had recently begun my doctoral studies and there I was, in the Royal College of Art studios, trying to make a start with an academic project on queer representation. My friend Ruth had agreed to sit for me and together we set up the studio. Once I placed a piece of masking tape on the floor, Ruth positioned themselves just behind, ready for the first frame. I had brought with me a handful of printouts from photobooks that I thought could serve as inspiration, amongst these Claude Cahun’s self-portrait in suit from the 1920s. While Cahun posed for their camera with their hand on their hip, Ruth posed for mine in profile, raising their chin and gaze to meet mine from the other side of the camera bellows.

Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2015

Large Format Photography

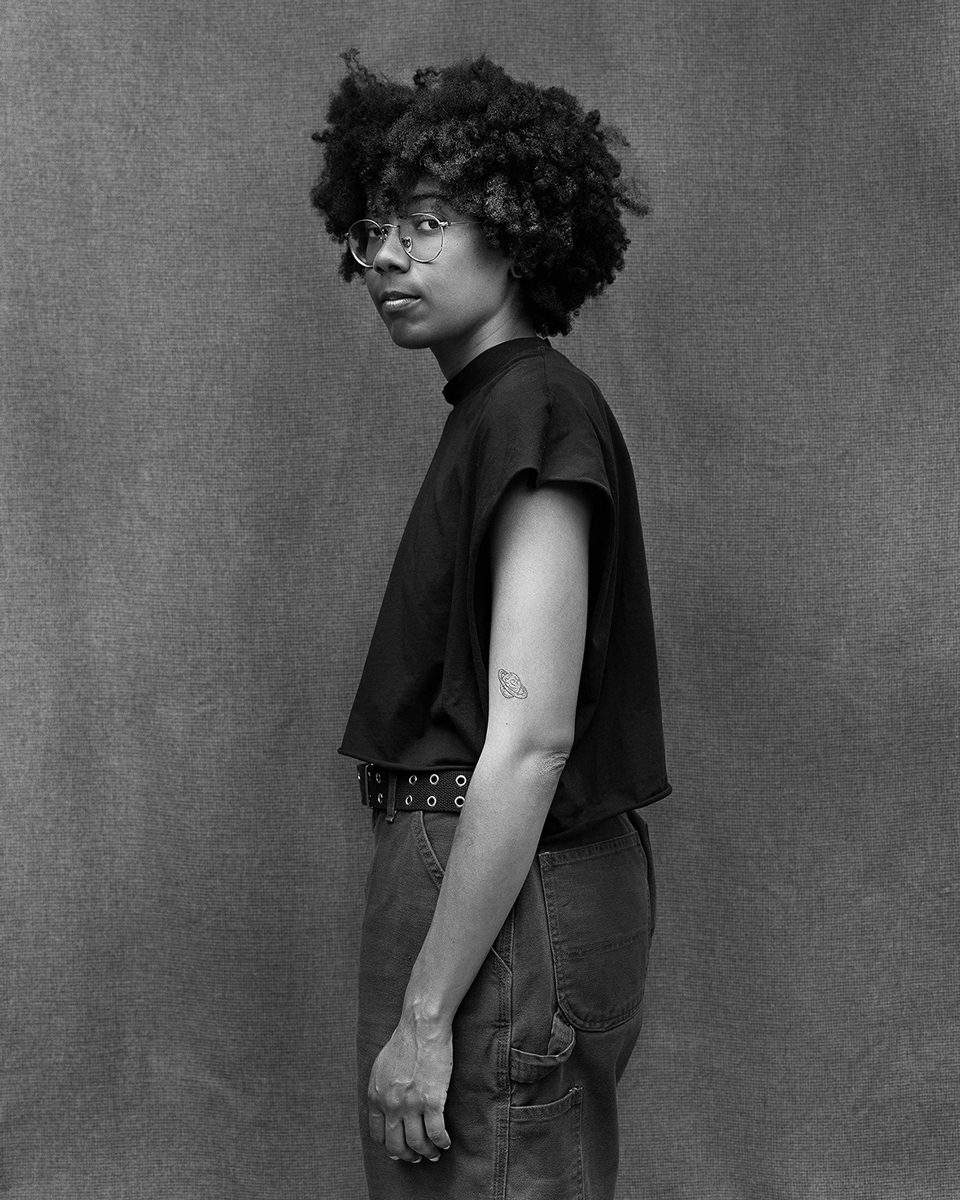

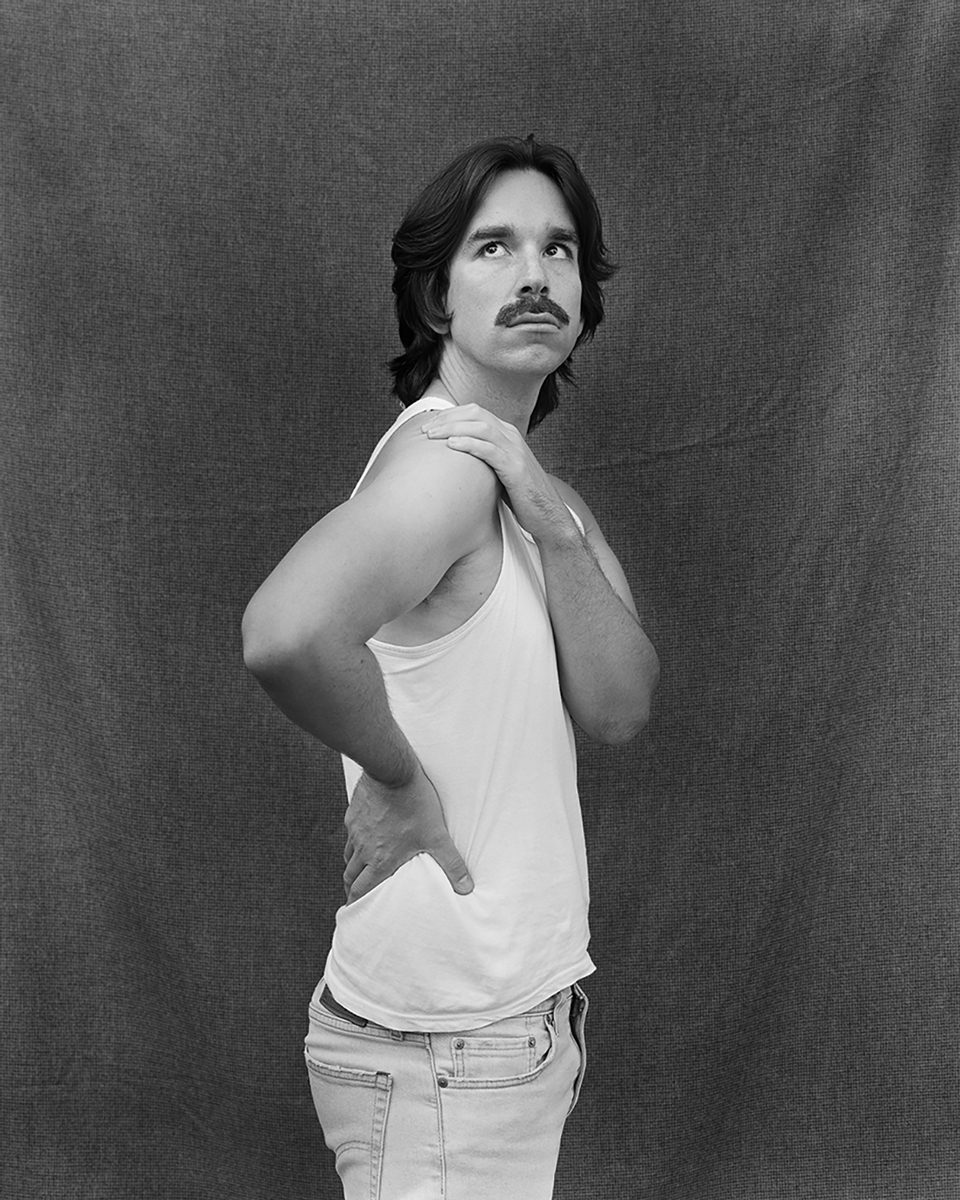

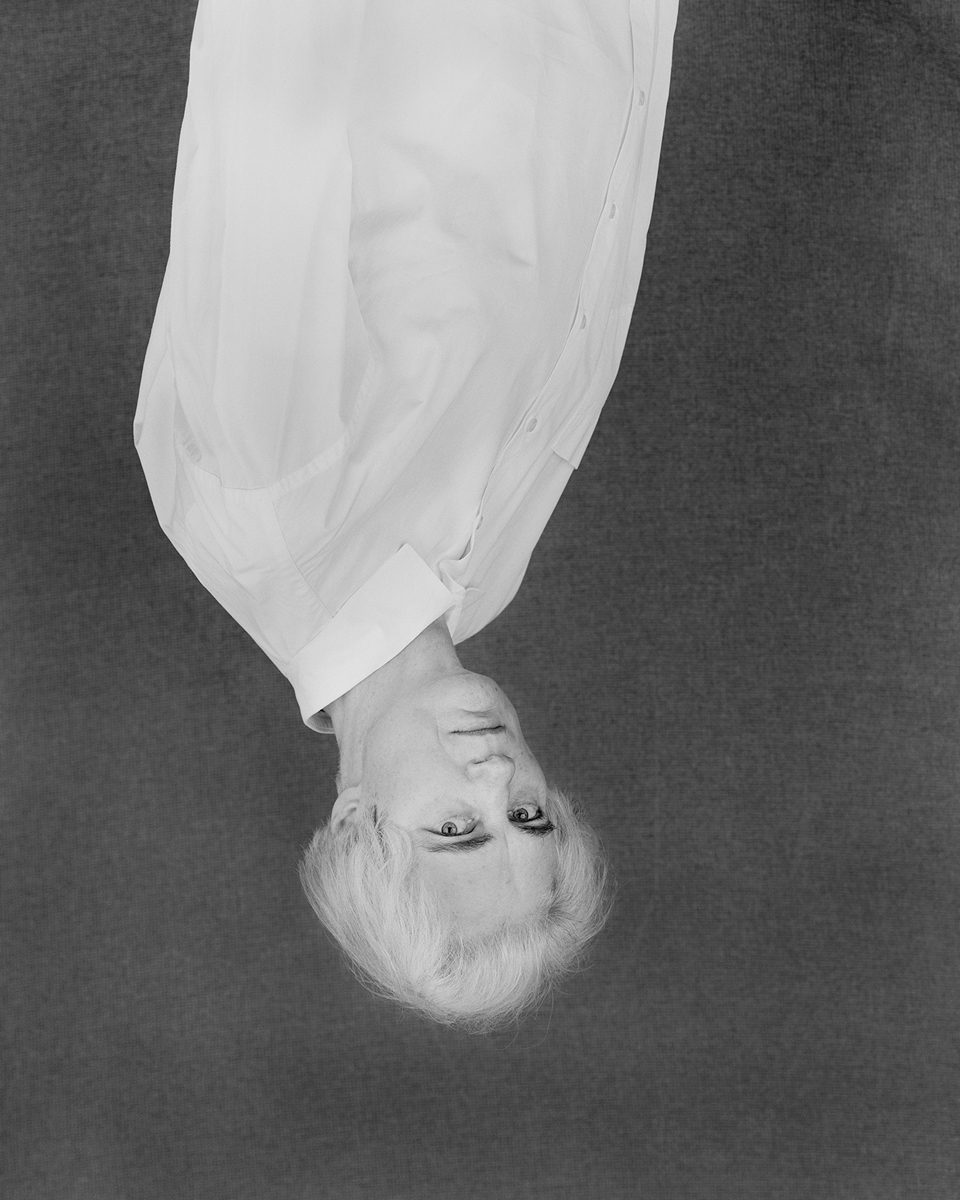

I take my photographs with a Cambo monorail 5x4” camera and a 180mm f/5.6 Schneider lens and I shoot on ILFORD HP5+ 5x4” sheet film. That’s all I ever used, once I moved on from medium to large format photography. Little did I know that first day in 2015 that both camera and sheet film would come to play significant roles, not only in the actual physical materialisation of photographs but also in the conceptualisation of the project. The Queering of Photography soon developed into a project not only concerned with norms of identity but with norms connected to the photographic portrait, posing the question: what qualifies as a ‘good’ portrait? Shooting with a 5x4” camera demands attention to shutter and aperture (there are no automatic settings) as well as to the composition. The camera has no mirror which means that when I look through the camera’s ground glass (viewfinder), the person I photograph appears upsidedown. The manual process is slow and has welcomed a collaborative approach to picture making.

- Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2021

- Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2015

Subversive Stance

The large format portrait is by necessity collaborative in that it requires a dialogue: I give instructions to pose and gaze and the sitter responds and make suggestions. Each portrait from The Queering of Photography conveys something special: a glance, a tiny tattoo, creases in a shirt, an awkward poise, a turned neck. Sometimes our play with gesture and portrait conventions generates peculiar forms of subversions by turning the face away from the camera or presenting the portrait upsidedown. I understand these experiments to be homages, first to the collaborative approach to portraiture, second to the term queer as a subversive stance, and third to my mirrorless Cambo monorail camera.

Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2021

Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2018

Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2016

Representation

While these black and white portraits developed within the frames of academia, they have gradually gained their own autonomy. 2023 marks eight years since that initial shoot with Ruth and their portrait is still a favorite of mine with its self-confident gaze and hesitant posture. The Queering of Photography is at the same time a representation of the LGBTQ+ community in London, portraits of individual people, collaborative studio portraits, and playful gestures – all filtered through a monochrome sensibility.

- Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2021

- Åsa Johannesson, Looking Out, Looking In from The Queering of Photography, 2022

Images - ©Åsa Johannesson

About The Author

Åsa Johannesson

Åsa Johannesson is a Swedish London based artist working with large format portraiture and writing. With her work Åsa explores the relationship between queer identity, representation, and photographic materiality. Recent exhibitions include The Queering of Photography at Centrum for Fotografi, Stockholm (SWE); Peckham 24 at Copeland Gallery, London (UK) and Looking Out, Looking In at Landskrona Foto Festival, Landskrona (SWE). Åsa has an MA and a PhD from the Royal College of Art and is a Senior Lecturer in Photography at the University of Brighton. Her book Queer Methodology for Photography (Routledge) is published in December 2023.

Insta: @asajohannes

Website: https://asajohannesson.com/